Early history

From the 16th century to the 19th century

19th century Wembley

Railways and trams

Wembley Urban District

Wembley Park

The first Cup Final at Wembley

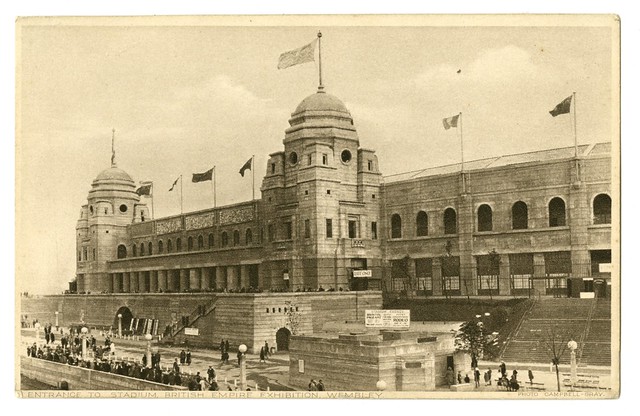

The British Empire Exhibition

Suburban growth

Arthur Elvin saves the Stadium

Industry

The Second World War

The 1948 London Olympics

Wembley Arena

Wembley Stadium

Places of worship

Post-war Wembley

The London Borough of Brent

The rise and fall of the shopping centre

Wembley today

Local history articles

Archive copies

Wembley is in south-eastern Brent, east of Sudbury, north of Alperton, west of Neasden and south of Kingsbury and Preston. Tokyngton is in eastern Wembley, south of the Chiltern Railway Line.

Early history

‘Wemba lea’ is first mentioned in a charter of 825. The name means ‘Wemba’s clearing’. The clearing the Anglo-Saxon Wemba chose, later the large triangular Wembley Green, was situated on and around a 71-metre hill. Wembley village grew up on the hill and on the future Harrow Road south of it. The surrounding area remained woodland for much of the middle ages.

Tokyngton, southeast of Wembley, means ‘the farm of the sons of Toca’. In 1086, at the time of the Domesday Book (which recorded a survey of land in England and Wales), the district was one of the most populated parts of Harrow parish.

Records first mention Tokyngton by name in 1171. By about 1240, there was a chapel there dedicated to St Michael, and there is evidence that it had a vicar. The chapel, which was situated south of the present-day South Way (next to Wembley Stadium Railway Station), provided an easier alternative to Harrow Church, which was a long walk away and at the top of a hill. However, local people needed to go to Harrow to shop at Harrow Market, which begun in 1261 and was apparently held in Harrow Churchyard. It lasted until the end of the 16th century.

Wembley and Tokyngton manors were both sub manors of Harrow and, initially, Tokyngton was more important than Wembley. Tokyngton Manor formed in the late 13th century, from estates owned by the Barnville family. The Barnvilles had a house at Tokyngton by 1400, with the manor house built around 1500. By 1528, the manor had passed to the Bellamy family. By 1759, Tokyngton Manor was still a farm.

Flick through this album of old photos of Wembley and Tokyngton from the Brent Museum and Archives collection: